October 2012

With the fine autumn weather, I was keen to get outside again, with a rare Thanksgiving weather window. Up to this point in the fall, I had spent most of my weekends in the mountains. I think this might stem from a major withdrawal last winter, when poor weather kept most of my trips at treeline or below. But with a stream of sunny weekends, I was starting to run out of ideas. Just as I was beginning to worry about spending a long weekend cragging in the sun, Lena suggested a visit to the Judge. Mount Judge Howay, an often desired, but rarely visited summit. The Judge? Seriously?!? What about the canoe, or the river crossing, or the notorious bushwack from sea level?

These were the thoughts going through my head as I replied, “I like this Judge idea…” “Let’s go get Judged!” she responded. And just like that, I searched the internet for any information I could find. This wasn’t hard, stories of trips to the Judge are easy to come by. One can search Mount Judge Howay failure and find a disproportionate number of old trip reports describing river crossing epics. In fact, most failures come in the initial stages of this trip, rather than a particularly hard section on the summit.

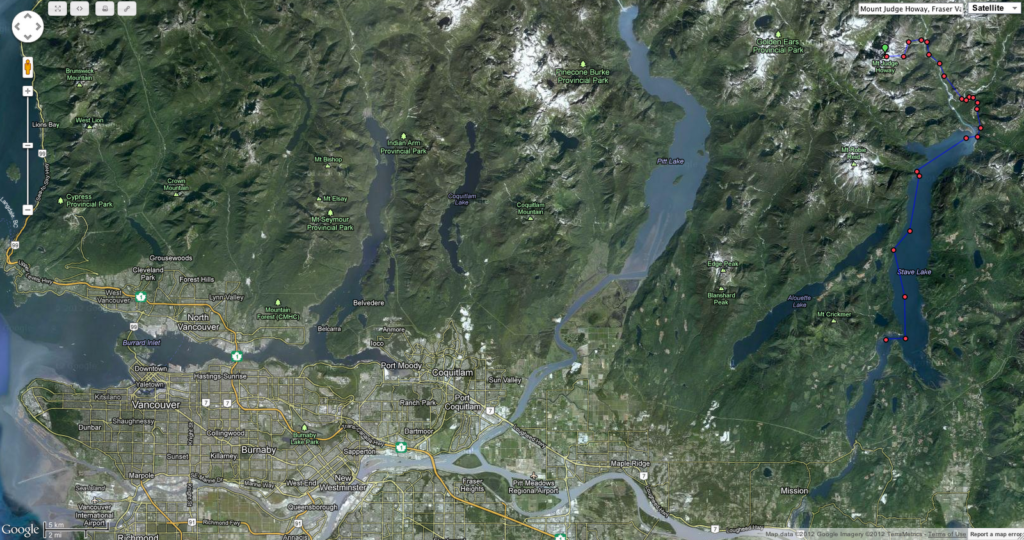

The Judge. A coastal classic, so close to home. A multi-day multi-modal journey. Mount Judge Howay is a prominent double-peaked summit in the Fraser Valley, easily recognized from surrounding peaks near and far. It’s one of those peaks that you can stare at for a while, thinking about how great the view from the top would be, but then as you recount the complicated approach, you quickly change your mind to something with easier access.

The whole thing seemed ridiculous, but then again, we’re dealing with Lena Rowat here. She is no stranger to coastal adventures, having skied the entire length of the Coast Range. If there was a partner for this trip, she was it. Lena picked me up on Friday afternoon, and we headed off to a Karl’s place in Deep Cove to pick up the canoe. This wasn’t just any ordinary canoe though, this was the legendary canoe used by Karl and Damien on their week-long self-propelled trip to the Judge. We drove east for an hour and a half on Highway 1 and then Dewdney Trunk Road to get to Stave Lake. In the past, visitors to the Judge have launched their canoes off Cypress Point on the east side of Stave Lake, but a pulled bridge has made that access unfeasible, unless you like walking with your canoe and gear down old logging roads. Our plan was to launch from Sayers Point. We turned off onto the Florence Lake road on the west side. It was dark by this point, and we headed off into the heart of redneck country.

I did not have a good idea of where we would park. To the south of Sayers Point, there are extensive mud flats which dry out in the summer. The flats are popular with partiers and their ATVs and dune buggys. It didn’t seem like a safe spot to leave the car. Reluctantly, we left the car on the edge of the mudflats, after some advice from a group who said they would look after our car and that it was less likely to get torched on the beach versus on the road. We would joke about this over the next couple days, wondering whether we would come back to a skeleton of a car.

We emptied the car and loaded the canoe on the beach. This included our overnight gear, two bicycles and one rubbermaid container, which is Lena’s trademark packing method. We paddled off into the darkness, the nighttime silence broken by the cracking noise of fireworks and roar of two-stroke engines in the near distant. Two hours later, partially guided by the reflected glow of the moon on the ripply waters, we pulled ashore at the Stave Lake Powerhouse. It was already midnight by the time we had the tent up on the access road. For those wondering, the access road is likely gated the top where it joins the Florence Lake road, 200m above the lake. We camped at the Powerhouse to get away from the noise at the mud flats, and to give ourselves a slight head start the next morning. It was October after all, the days are short.

To make the most of the short fall days, we woke up before sunrise each day. By day break, we were paddling north again towards the end of Stave Lake. We paddled against a northerly outflow, with gusts which seemed to stall our forward progress with every stroke. A motorized canoe would be perfect here. I don’t have a good track record with canoe-approached mountaineering. Four years ago, Tim and I tried to paddle down Chilko Lake, but we where turned around by strong winds. Slowly, we worked our way up the western shoreline. We beached the canoe at Glacier Bay at the northwest corner of Stave Lake to thaw our cold fingers in the sunshine.

The north end of Stave Lake is a strange sight to the eye. Prior to the damming of the lake in the early 1920’s, massive cedars grew in the valley. These trees were left behind in the river, and later logged in the 80’s during periods of prolonged lowering of the reservoir. We paddled through the shallow waters, barely floating over top of giant stumps. There might have been one or two soft landings. We worked our way eastward through shallow sand flat, eventually reaching the road at the 4 Km marker. While the paddling through the forest was scenic, the faster option is to go ashore at the southern terminus of the road, where the logging barge docks and then continue on bikes from there.

The next stage of our multi-modal journey took us on our bikes north along the Stave FSR. We biked north for ten kilometres along a nearly flat gravel road, only stopping to stare at the steep rugged terrain in our new world. So close to home, yet so far. We left our bikes at the 14 Km marker, and prepared ourselves for the fording of the Stave River. If you search online, there are some great stories of successful and unsuccessful crossings, stories of broken paddles and sinking rafts, and bike trailer contraptions to haul the canoe along the road. Luckily for us, the water levels in the fall are low, and it was an uneventful knee deep wade across. Check the water levels beforehand on this handy website before committing to a ford. If you’ve read this far, you should know that you need a perfect weather window for this trip.

The notoriety behind the climb of the Judge lies in the next six hundred vertical metres, but thanks to a collective effort of coastal bushwackers, a flagged route weaves it way through devil’s club, slide alder, steep forest and cliff bands. Has anybody been up this way recently? Please feel free to comment below!

Don’t try to pick your own route through here, this isn’t the place for that, just follow the flagging. We lost the flagging at first, stumbled through unnecessary alder, but soon trended left and regain the flagging and made slow progress up through the trees, grabbing on cedar branches where necessary to pull up and over rock steps. We climbed up through this patch of steep trees until it was possible to traverse left across the infamous water platform, a break in the gully allowing passage through an otherwise impassable gully. Did we just luck out? I like to think I could find the flagging, bushwhack up to the water platform again, but with time, I think the flagging and route may fade.

From here, we worked our way towards the hanging valley which drains into another larger gully to the south. Getting out of the water platform proved to be some of the most tedious bushwacking of the trip. The south side of the gully was blockaded by trees fallen over from an avalanche during the winter. We crawled through the trees, while pine needles accumulated inside my shirt. Words fail to describe the tedious motion of climbing through a tree, snagging your pack, clearing your face of pine needles, looking up and down, and wondering when it’ll all be over.

We contoured through some old growth after, and then we were finally looking down into the hanging valley. However, a swath of slide alder stood in our path. It wasn’t clear on the best way to get around this, so we continued hiking uphill between the alder and the cliff band to our right, working our way through the top of the path until reaching another slabby gully. At this point, we dropped down to our left through some trees and slide alder, losing 50-100m of elevation along the way. However, compared to the fallen trees, this seemed trivial.

It was difficult to lose that elevation after working so hard to gain it. By this point, we had been bushwacking for four hours, tired and ready for a break. We pitched the tent on some granite slabs at ~660m, and settled in for a dinner of mashed potatoes.

At daybreak, we left camp and looked for a route through the granite slabs which surround the hanging valley. Hindsight is always 20/20, we did not take the best route here. We worked our way across firm snow, then off into the moat behind the snowfield towards the main gully at the end of the valley. Eventually the small moat transformed into a dark cavernous abyss, and we moved onto the slabs. As in, we actually climbed the slab underneath the snow.

The plan was to climb the slabs, reach some trees above, and then hope for a route through the head of the main gully. A few committing moves on the slab were required, and I hoped that our route would go, as retreat here seemed difficult. Our gamble worked, and we found a spot at the top where the vertical sides of the gully flattened. Once across the main gully (which would be completely snow filled in the spring and early summer and easy bootpacking), we hiked south across boulders and slabs and heather slopes, feeling relieved to finally be moving in easier terrain.

The remainder of the climb up to the summit plateau was straightforward talus or scree hiking mixed with sections of firm snow where we used crampons. I brought steel crampons, while Lena took instep crampons. The standard route goes up a broad east-facing gully, with a bottleneck near the top where the gully steepens and narrows. Would it go? Or would be we blocked by steep unclimbable snow or loose rock? My worries turned out to be unnecessarily, and it was easy scrambling on ledges on the sides, with some minor loose rocks.

Looking back at the photo above, it seems quite clear that the left summit is the higher north peak, whereas the right summit is just a subsidiary summit. Perhaps I was tired, but when I climbed to the col between the two peaks, it seemed like the right peak was higher, so we started scrambling up that one. The rock was solid, featured but steep. Lena continued climbing higher, so I followed. The exposure was nauseating. At the top, we stared across at the true summit, wondering whether the dark blank wall in front of us was climbable.

We retreated off the summit with the aid of a 15m rappel (we took a 30m rope) and climbed back up to the col and over to the main summit. What looked like an improbable face now appeared climbable. I pulled out the climbing gear just in case. Ironically, the climbing was much easier. There was one short step above the snow bridge spanning the moat, and after that it was easy 4th class on very featured slabs.

At 2pm, we were standing on the summit. I’ve been wondering what the view from the top would be like for a long time. There was no disappointment today on a clear gorgeous October afternoon. From the top, I could see the North Shore mountains, the Golden Ears, Robie Reid, the Misty Icefields, the Chehalis, Mount Baker, Shuksan, Sleese, Old Settler, Urquhart, Tantalus, Garibadi, Mamquam, Matier, and the list goes on!

We reversed our route down the slab, then the snowfield and gully back to the head of the hanging valley. This time though, we were going to pick a route through the south side of the valley instead. We descended slabs, working our way east until we found the side gully as described in one of the route descriptions I had. Hindsight is 20/20. I wasn’t sure what the author meant by a side gully, but this was clearly an indistinct gully on the looker’s left side of the gully forming the valley.

This side gully leads into a ramp system that first goes left then back right to exit the valley. This route was much better than what we used in the morning. The last challenge was crossing the snow bridges between us and camp. With the hot weather this summer, massive gaps had formed below the snow where torrents of water eroded away at the winter snowpack. Again, I was scared, and whimpered my way back to camp, while Lena, coastal explorer and all, walked down nonchalantly. Dinner was mashed potatoes again, it was Thanksgiving after all.

BW4 difficulty as “Severe brush. Pace less than one mile per hour. Leather gloves and heavy clothing required to avoid loss of blood. Much profanity and mental anguish. Thick stands of brush requiring circumnavigation are required.”

Dale (2000) – Alpine Club of Canada May 2000 Newsletter

The trip home felt much easier the next day. The bushwacking felt easier and the river crossing was trivial. We were back at the canoe before noon. At this point, I got a little extra motivation for the canoe home.

“There’s a chance that we could make it back on time for this Thanksgiving dinner that my friend’s are having,” said Lena.

“Really? Why didn’t you tell me earlier?” I replied.

I knew why though, I’m sure we would have been bushwacking at 4am if I had known. I paddled as hard as I could for the next four hours. We found our car intact at Sayer’s Point, dropped off the canoe in Deep Cove, and proceeded to feast on a dinner of turkey, stuffing, salads, roast vegetables, spicy beans, more mashed potatoes, and of course, pumpkin pie.

I would love to hear from you if you have been up to Mount Judge Howay since my trip in 2012. I’ll add any pertinent information to this post to aid anybody willing to suffer. – Rich

Excellent report! We hope to repeat this ourselves in the near future. Awesome!

Hi, I am attempting this trip in October hopefully during a nice weather window. Would you happen to have a GPS track for your route?

Hey Jon! Sorry this was done pre-gps tracking days for me. Good luck!